Credits

This doc has been adapted from Mikhail Shilkov’s blog entry Monads explained in C# (again). It attempts to explain the rationale behind Monads, providing simple examples showing how they relate to standard library constructs.

Intro

I love functional programming for the simplicity that it brings.

But at the same time, I realize that learning functional programming is a challenging process. FP comes with a baggage of unfamiliar vocabulary that can be daunting for somebody coming from an object-oriented language like Kotlin.

some of the functional lingo

Monad is probably the most infamous term from the list above. Monads have the reputation of being something very abstract and very confusing.

The Fallacy of Monad Tutorials

Numerous attempts were made to explain monads in simple definitions. And monad tutorials have become a genre of its own. And yet, time and time again, they fail to enlighten the readers.

The shortest explanation of monads looks like this:

A Monad is just a monoid in the category of endofunctors.

It’s both mathematically correct and totally useless to anybody learning functional programming. To understand this statement, one has to know the terms “monoid”, “category” and “endofunctors” and be able to mentally compose them into something meaningful.

The same problem is apparent in most monad tutorials. They assume some pre-existing knowledge in the heads of their readers, and if that assumption fails, the tutorial doesn’t click.

Focusing too much on mechanics of monads, instead of explaining why they are important, is another common problem.

Douglas Crockford grasped this fallacy very well:

The monadic curse is that once someone learns what monads are and how to use them, they lose the ability to explain them to other people

The problem here is likely the following: Every person who understands monads had their own path to this knowledge. It hasn’t come all at once. Instead, there was a series of steps, each giving an insight, until the last final step made the puzzle complete.

But they don’t remember the whole path anymore. They go online and blog about that very last step as the key to understanding, joining the club of flawed explanations.

There is an actual academic paper from Tomas Petricek that studies monad tutorials.

I’ve read that paper and a dozen of monad tutorials online. And, of course, now I came up with my own.

I’m probably doomed to fail too, at least for some readers.

Story of Composition

The base element of each functional program is Function. In typed languages, each function is just a mapping between the type of its input parameter and output parameter. Such type can be annotated as func: TypeA -> TypeB.

Kotlin is a hybrid functional / object-oriented language, so we use top level functions or methods to declare functions. There are two ways to define a method comparable to function func above. I can use a top level “static” function:

class ClassA

class ClassB

fun func(a: ClassA): ClassB = TODO()

… or an instance method:

class ClassA {

// Instance method

fun func(): ClassB = TODO()

}

The top level form looks closer to the function notation, but both ways are actually equivalent for the purpose of our discussion. I will use instance methods in my examples, however all of them could be written as top level extension methods too.

How do we compose more complex workflows, programs, and applications out of such simple building blocks? A lot of patterns in both OOP and FP worlds revolve around this question. And monads are one of the answers.

My sample code is going to be about conferences and speakers. The method implementations aren’t really important. Just watch the types carefully. There are 4 classes (types) and 3 methods (functions):

class Speaker {

fun nextTalk(): Talk = TODO()

}

class Talk {

fun getConference(): Conference = TODO()

}

class Conference {

fun getCity(): City = TODO()

}

class City

These methods are currently very easy to compose into a workflow:

fun nextTalkCity(speaker: Speaker): City {

val talk = speaker.nextTalk()

val conf = talk.getConference()

val city = conf.getCity()

return city

}

Because the return type of the previous step always matches the input type of the next step, we can write it even shorter:

fun nextTalkCity(speaker: Speaker): City =

speaker

.nextTalk()

.getConference()

.getCity()

This code looks quite readable. It’s concise, and it flows from top to bottom, from left to right, similar to how we are used to reading any text. There isn’t much noise either.

That’s not what real codebases look like though, because there are multiple complications along the happy composition path. Let’s look at some of them.

Nullability

When interacting with Java or other languages whose function may return null with any type hints any value returned can be null.

In the example above, I might get runtime errors if one of the methods ever returns null back.

Typed functional programming always tries to be explicit about types, so I’ll re-write the signatures of my methods to annotate the return types as nullables:

class Speaker {

fun nextTalk(): Talk? = null

}

class Talk {

fun getConference(): Conference? = null

}

class Conference {

fun getCity(): City? = null

}

Now, when composing our workflow, we need to take care of null results:

fun nextTalkCity(speaker: Speaker?): City? {

if (speaker == null) return null

val talk = speaker.nextTalk()

if (talk == null) return null

val conf = talk.getConference()

if (conf == null) return null

val city = conf.getCity()

return city

}

It’s still the same method, but it has more noise now. Even though I used short-circuit returns and one-liners, it still got harder to read.

To fight that problem, smart language designers came up with the Safe Call Operator:

fun nextTalkCity(speaker: Speaker?): City? =

speaker

?.nextTalk()

?.getConference()

?.getCity()

Now we are almost back to our original workflow code: It’s clean and concise, but we still have 3 extra ? symbols hanging around.

Let’s take another leap.

Errors

Quite often, a function returns a success or an error, not just a null value as we did before. To some extent, that’s a generalization of null case: With T?, we might get 0 or 1 results back, while, with something like Either or an similar type, we can get failure or success results.

Our sample API could look like this:

import arrow.core.Either

import arrow.core.Either.Left

object NotFound

class Speaker {

fun getTalk(): Either<NotFound, Talk> =

Left(NotFound)

}

class Talk {

fun getConference(): Either<NotFound, Conference> =

Left(NotFound)

}

class Conference {

fun getCity(): Either<NotFound, City> =

Left(NotFound)

}

How would we combine the methods into one workflow? The traditional version would look like this:

import arrow.core.flatMap

fun cityToVisit(speaker: Speaker): Either<NotFound, City> =

speaker

.getTalk()

.flatMap { talk -> talk.getConference() }

.flatMap { conf -> conf.getCity() }

It still reads ok-ish. But the combination of flatMaps can get unreadable pretty fast, specially in a more complex model with further nesting. The exact workflow might be lost in the mechanics.

Let me do one additional trick and format the same code in an unusual way:

fun cityToVisit(speaker: Speaker): Either<NotFound, City> =

speaker

.getTalk() .flatMap { x -> x

.getConference() }.flatMap { x -> x

.getCity() }

Now you can see the original code on the left, combined with just a bit of technical repetitive clutter on the right. Hold on, I’ll show you where I’m going.

Let’s discuss another possible complication.

Asynchronous Calls

What if our methods need to access some remote database or service to produce the results? This should be shown in type signature,

and we can imagine a library providing a Task<T>, IO<A>, Mono<A> type for that.

Luckily in Kotlin we have suspend functions which fix the problem of nesting and callbacks all around.

Kotlin suspension is an ideal place to use monads because it allows imperative and direct syntax over monadic data types without the burden of flatMap chains.

class Speaker {

suspend fun nextTalk(): Talk = TODO()

}

class Talk {

suspend fun getConference(): Conference = TODO()

}

class Conference {

suspend fun getCity(): City = TODO()

}

This change fixes our nice workflow composition again.

suspend fun nextTalkCity(speaker: Speaker): City {

val talk = speaker.nextTalk()

val conf = talk.getConference()

val city = conf.getCity()

return city

}

or simply

suspend fun nextTalkCity(speaker: Speaker): City =

speaker.nextTalk().getConference().getCity()

You can see that, once again, it’s our nice, readable workflow.

Pattern

Can you see a pattern yet?

I’ll repeat the T?, Either<NotFound, T>, suspend () -> T-based workflows again:

fun nextTalkCity(speaker: Speaker?): City? {

return

speaker ?

.nextTalk() ?

.getConference() ?

.getCity()

}

fun allCitiesToVisit(speaker: Speaker): Either<NotFound, City> {

return

speaker

.getTalks() .flatMap { x -> x

.getConferences() }.flatMap { x -> x

.getCities() }

}

suspend fun nextTalkCity(speaker: Speaker): City {

return

speaker

.nextTalk()

.getConference()

.getCity()

}

In the first 2 cases, there was a complication that prevented us from sequencing method calls fluently.

In the last case with suspend functions we have the maximum expression and simplification where we observe there is no need to call flatMap or create any callbacks.

Kotlin suspend is a form of the Continuation monad from which other monads can be generalized and composed thanks to its async and concurrent capable nature.

Using suspend callback and completion features Arrow is able to bring direct syntax to all these monadic data-types.

Let’s try to generalize this approach from the very beginning.

Given some generic container type WorkflowThatReturns<T>, we have a method to combine an instance of such a workflow with a function that accepts the result of that workflow and returns another workflow back:

class WorkflowThatReturns<T> {

fun addStep(step: (T) -> WorkflowThatReturns<U>): WorkflowThatReturns<U>

}

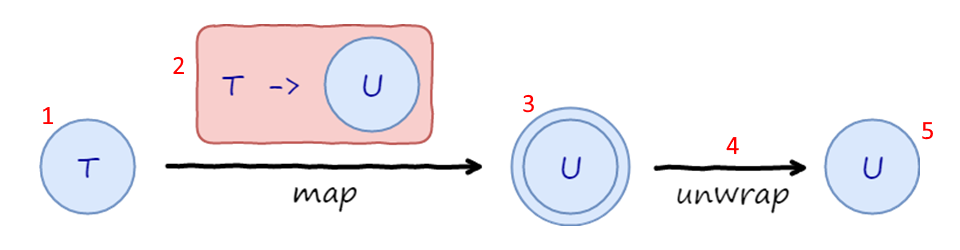

In case this is hard to grasp, have a look at the picture of what is going on:

An instance of type T sits in a generic container.

We call addStep with a function, which maps T to U sitting inside yet another container.

We get an instance of U, but inside two containers.

Two nested containers are automatically flattened into a single container to get back to the original shape.

Now we are ready to add another step!

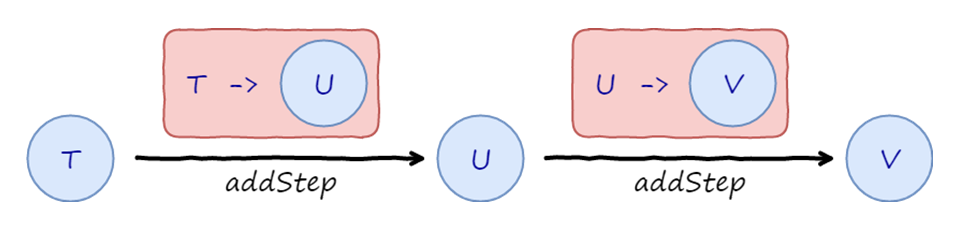

In the following code, nextTalk returns the first instance inside the container:

fun workflow(speaker: Speaker): WorkflowThatReturns<City> {

return

speaker

.nextTalk()

.addStep { x -> x.getConference() }

.addStep { x -> x.getCity() }

}

Subsequently, addStep is called two times to transfer to Conference and then City inside the same container:

Finally, Monads

The name of this pattern is Monad.

In Arrow terms, a Monad can be implemented by means of the Effect interface.

The Effect interface defines the ability to have a scope in which a coroutine can be used to complete the context or yield a value.

fun interface Effect<F> {

fun control(): DelimitedScope<F>

}

We can then define specific effects for our data types that implement Monad bind.

import arrow.continuations.Effect

fun interface NullableEffect<A> : Effect<A?> {

suspend fun <B> B?.bind(): B =

this ?: control().shift(null)

}

Monad bind is then implemented by shifting out of the context with null if the value being bound happens to be null or yielding the value by returning it if not null.

control().shift(value) can be seen as a functional throw. Once we pass a value the context of our Effect will exit with value.

With control().shift based on the Effect interface we can implement monad bind short-circuiting and other patterns supported by the Continuation monad for arbitrary data types.

object nullable {

operator fun <A> invoke(func: suspend NullableEffect<*>.() -> A?): A? =

Effect.restricted(eff = { NullableEffect { it } }, f = func, just = { it })

}

The argument just in Effect is used to put the result of the computation expression in the Effect we are modeling, in this case nullability and absence typed as A?.

In the example above we saw that in order to form a Monad we need a just constructor used in the effect block and an implementation for suspend bind declared in a subtype of the Effect interface.

The Effect interface provides a restricted scope for pure computations that do not require suspension and a suspended block for those that do require suspension.

Finally we can use our new nullable effect block, and its bind function to compute over the happy path of nullable typed values.

suspend fun nextTalkCity(maybeSpeaker: Speaker?): City? =

nullable {

val speaker = maybeSpeaker.bind()

val talk = speaker.nextTalk().bind()

val conf = talk.getConference().bind()

val city = conf.getCity().bind()

city

}

Even though I spent quite some time with examples, we expect you to be slightly confused at this point. That’s ok.

Keep going and let’s have a look at several sample implementations of the Monad pattern.

Option

My first example was with nullable ?. The full pattern containing either 0 or 1 instance of some type is called Option (it might have a value, but might not).

While nullable types are faster, Option is still required in some cases for interoperability with Java and polymorphism where you may want to represent nesting with Option<Option<A>>. Having said that we still recommend you use nullable types over Option where possible as the Kotlin language provides direct support for them in the type system.

Option is yet another approach to dealing with absence of a value, an alternative to the concept of null. You can read more about Option to see how Arrow implements it.

When null is not allowed, any API contract gets more explicit: Either you return type T and it’s always going to be filled, or you return Option<T>.

The client will see that Option type is used, so it will be forced to handle the case of absent value.

Given an imaginary repository contract (which does something with customers and orders):

import arrow.core.Option

import arrow.core.None

data class Customer(val addressId: Int)

data class Address(val id: Int, val lastOrder: Option<Order> = None)

data class Order(val id: Int, val shipper: Shipper = Shipper)

object Shipper

interface OptionRepository {

fun getCustomer(id: Int): Option<Customer> = None

fun getAddress(id: Int): Option<Address> = None

fun getOrder(id: Int): Option<Order> = None

}

The monad bind behavior can be written without flatMap in a direct style:

fun interface OptionEffect<A> : Effect<Option<A>> {

suspend fun <B> Option<B>.bind(): B =

fold({ control().shift(None) }, { it })

}

object option {

operator fun <A> invoke(func: suspend OptionEffect<*>.() -> A?): Option<A> =

Effect.restricted(eff = { OptionEffect { it } }, f = func, just = { Option.fromNullable(it) })

}

suspend fun OptionRepository.shipperOfLastOrderOnCurrentAddress(customerId: Int): Option<Shipper> =

option {

val customer = getCustomer(customerId).bind()

val address = getAddress(customer.addressId).bind()

val lastOrder = address.lastOrder.bind()

val order = getOrder(lastOrder.id).bind()

order.shipper

}

We observe here how in the same way we implemented and used monad comprehensions for nullable types, we now implement the same Monad pattern, this time over Option. Fortunately Arrow already provides all these effect builders for all the data types that support monadic behavior.

Abstraction for all Monads

We’re going to dispel one common misconception. Sometimes the word Monad is used to refer to types like Option, Future, Either, and so on, and that’s not correct. Those are called data-types or just types. Let’s see the difference!

As you have seen, neither A? nor Option implement Monad directly. Their actual bind and just capabilities are described by implementing the Effect interface.

This is intentional, as you can potentially have several Monad implementations for a single type or even mix non-monadic effects inside Effect interfaces in order to provide more expressive DSLs. This is notorious in the actual Arrow implementations where effects such as Either can perform different forms of monad bind over multiple types like Either and Validated using the same idioms.

Arrow specifies that Monad capabilities must be implemented by a separate object or class in terms of the Effect interface, referred to as the “instance of Monad for type F” or “computation expression for F”.

More info on binding and effects is available at Computation Expressions and Monad Comprehensions, and you can find a complete section of the docs explaining it.

Monad Laws

A typical monad tutorial will place a lot of emphasis on the laws, but we find them less important to explain to folks learning about Monads for usage purposes. Nonetheless, here they are for the sake of completeness or for those cases where you wish to implement your own monad or Effect instances.

There are a couple laws that the just constructor and bind need to adhere to consider the Effect a Monad with a stable implementation.

These laws are encoded in Arrow as tests and are already applied on all Effect instances in the library.

Let us re-write the laws in effect-notation. effect here represents either, option or any effect implementing suspend bind and a constructor here represented as just.

Left Identity law says that Monad constructor is a neutral operation: You can safely run it before bind, and it won’t change the result of the function call:

To demonstrate the laws we will use this version of the Identity monad and we will name it Just.

Unlike Option, Either and other types here Just has no effect and simply models access to the identity of a value of type A

data class Just<out A>(val value: A)

fun interface JustEffect<A> : Effect<Just<A>> {

suspend fun <B> Just<B>.bind(): B = value

}

object effect {

operator fun <A> invoke(func: suspend JustEffect<*>.() -> A): Just<A> =

Effect.restricted(eff = { JustEffect { it } }, f = func, just = { Just(it) })

}

Left identity:

Let’s define x && f as

fun f(x: Int): Just<Int> = Just(x)

val x = 1

then

effect {

val x2 = Just(x).bind()

f(x2).bind()

}

is the same as

effect {

f(x).bind()

}

Right Identity law says that, given a monadic value, wrapping its contained data into another monad of same type and then bind it doesn’t change the original value:

Right identity:

Given m defined as

val m = Just(0)

then

effect {

val x = m.bind()

Just(x).bind()

}

is the same as

effect { m.bind() }

Associativity law means that the order in which bind operations are composed does not matter.

Associativity:

Given m, f and g are defined as

val m = Just(0)

fun f(x: Int): Just<Int> = Just(x)

fun g(x: Int): Just<Int> = Just(x + 1)

All the 3 example below are the same

effect {

val y = effect {

val x = m.bind()

f(x).bind()

}.bind()

g(y).bind()

}

effect {

val x = m.bind()

effect {

val y = f(x).bind()

g(y).bind()

}.bind()

}

effect {

val x = m.bind()

val y = f(x).bind()

g(y).bind()

}

The laws may look complicated, but, in fact, they are very natural expectations that any developer has when working with monads, so don’t spend too much mental effort on memorizing them.

Conclusion

Don’t be afraid of the “M-word” just because you are a Kotlin programmer.

Kotlin has a notion of monads as predefined language construct through its suspension system and this gives us tremendous power to write monadic applications in direct style using suspend functions and continuations with Kotlin and Arrow.